Sanchu Iyer

Note: this blog is based on a longer article: “Deaf migration through an intersectionality lens” by Steven Emery and Sanchayeeta Iyer, in the journal Disability and Society. Open access: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09687599.2021.1916890

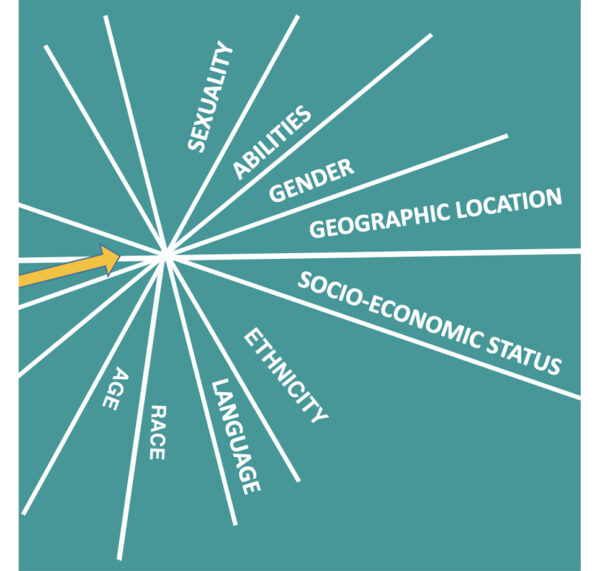

Intersectionality is a useful lens in our study of deaf mobilities. “Intersectionality” as a concept was coined by a black female academic called Kimberlé Crenshaw, to describe the intersection and interlocking relations of oppression based on race, gender, and class (the original triad). Later, this concept was expanded to include other forms of oppression (such as based on disability), which are experienced through multiple intersecting social positions.

In the context of migration in London, the intersectionality concept helps us to understand and demonstrate the complex web of power dynamics between various people and institutions that deaf migrants interact with, and to explore their impact on identities of deaf migrants. London is a superdiverse city, and the research was situated within the climate of hostility and insecurity in relation to the Windrush scandal and the Brexit process.

Visibility of deaf migrants in research

Only recently, researchers in migration studies began to acknowledge the lack of studies on the intersection of disability, ethnic minority status, and migration. Among the limited literature on disabled migrants, much is written about the vulnerable position of disabled refugees and asylum seekers as they migrated to countries such as the UK. However, within these studies of disabled migrants, it is hard to find information specifically about deaf migrants who are sign language users. The few studies of deaf migrants in London are focused on lack of support and access to services. In contrast, our research focused on everyday life experiences of deaf migrants in relation to their mobilities and social interactions in the city. Lack of access is a pertinent problem, but a focus on access does not capture the complexity of deaf migrants’ experiences. Using an intersectionality lens means we can bring forth otherwise invisible and marginalised narratives.

Deaf migrants as a category?

We are careful not to treat ‘deaf migrants’ as a fixed and stable category as there are diverse deaf migrants of various backgrounds that emigrated from various countries. Our interviewees came from countries from all over the world including Brazil, Ghana, Burundi, Romania, Somalia, Italy, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Lebanon, Canada, Czech Republic, Guatemala, and Norway. We interviewed deaf people of various backgrounds as regards ethnicity/race, religion, sexual orientation, class, education and employment status. However, in our study we focused mostly on migrants from less privileged backgrounds, and we want their marginalised experiences/narratives to be heard especially in the context of the hostile climate in the UK, where they experienced racism and xenophobia.

Deafness as principal oppression?

We challenge the notion that deafness is the principal oppression with the other experiences such as racism, sexism, and homophobia as additional. Overall, our main interest is to explore the interlocking relations of power that deaf migrants have experienced and not merely ‘add’ on migration as their identity. Multiple categories (such as migration status, ethnicity, class, nationality, religion, gender, and disability) are intersecting and entwined. In other words, the multiple bases of one’s experience all happen simultaneously and cannot be analysed separately.

Intracategorical and intercategorical approaches

In our research we employed an intercategorical approach in our intersectional analysis to foreground structural and institutional powers in relation to identities. An intercategorical approach examines the ways in which social categories are constructed by each other. Thus, we are able to demonstrate a connection between immigration policy and racism, which provides a key to understand the context of these deaf migrants’ narratives.

In contrast, an intracategorical approach focuses on explore differences and diversities within a specific group experiencing similar intersections (eg. Sanchu’s PhD focuses on young deaf female migrants from India).

Hawa and Samba

We will now illustrate the points above with experiences of two Black deaf African migrants in London: Hawa (F) and Samba (M).

After she emigrated to the UK from Somalia with her family when she was in her teens, Hawa’s family took her to the Home Office to go through the border control process. She experienced two main obstacles – 1. going through the border control (which is inherently racist) to secure legal rights to reside in the UK, and 2. interacting with immigration official without any access to communication support.

We moved here and my family took me to the Home Office but it was a really long process without access. I felt like the family dog, being dragged along and not knowing what was happening. There were these big meetings with lots of people, and I had no idea what they were talking about.

She was not allowed to have her sister to interpret for her during interviews, she was clueless what is going on and what have been discussed, and when they provided her with a male interpreter, (which is problematic given that she’s a Muslim woman) she could not understand his signing.

They made another appointment and again it was full of people and my sister and I had to sit there passively whilst they discussed my case. I really don’t know what they said, but I think (bearing in mind I couldn’t access any of the information) that the Home Office were objecting to my application a bit? I’m not sure. They seemed to be saying ‘why are you here?’ and not accepting me. My sister tried to contact a lawyer to support us, and with their help the Home Office accepted my application and I received written permission to stay in the UK.

The communication difficulties left her with the experience of being oppressed on the base of language, gender, migrant, deafness/disability, and race – all intersected and interlocked.

When Hawa settled in the UK, she was placed in a mainstream school where she was the only deaf person in the whole school.

So once we had that, I then started school. It was the local school near our home, and it was awful; I was the only deaf person there in a large school and did not have any access at all. For two years I had no education at all. I would just sit in the class with no idea what was happening.

Hawa was denied access to a sign language environment and continued experiencing limited emotional and mental satisfactory interaction with hearing students. Also, schools in working-class areas are historically experiencing budget cuts from local authorities, and are struggling to provide adequate services for their students. Often migrants of ethnic minorities move into working-class environments. If Hawa was a white migrant from a Commonwealth country, would her experience be different? For Hawa, institutionalised forms of audism, classism, racism are intersected with being a migrant.

Samba’s father had brought him to the UK from Sierra Leone, on the suggestion of his wife who is a British citizen. She felt that Samba would get a better education and future opportunity as a deaf person in the UK. After 10 years of living in the UK, he applied for a British citizenship. Even though the process of obtaining a British passport was straightforward due to having some privilege due to his father’s wife being British, the immigration system is inherent racist and Samba had to go through the eligibly criteria in becoming a British citizen:

I need a British passport so I can be a British citizen which would make access much easier for me personally and solve many problems, but I did feel oppressed by the process. It felt that Britain wanted me to deny my identity as an African, to become fully British, but I am still African.

Samba saw that British white deaf people had access to information and resources which he grew up lacking in a formerly colonised country and felt he had to work harder to get ahead.

I am Black, I’m deaf, and I saw British people as white and affluent – not wealthy, just normal for them. They had all this information. I was Black, deaf, ASL [American Sign Language] user, no BSL [British Sign Language]. None of the access to information that they had. It took me a long time to work it all out finding out how things work, and it wasn’t easy.

While he is from a formerly British colonised country, the sign language he had acquired when growing up was American Sign Language (ASL) as it is the dominant sign language in Sierra Leone. ASL was brought to his country through Church missionaries from the USA, though established deaf schools. Intersecting histories of British colonialism and American imperialism not only impacted his country but also the sign language that is used there.

Samba encountered racism by white deaf people being in the UK. He was threatened with a knife.

I was threatened. I remember a white deaf person, I thought they might be knowledgeable, and I was trying to communicate with them and learn from them and they wanted me out. They were so angry they threatened me with a knife. (…) They pointed a knife at me and I was so shocked. When I asked ‘why the knife?’ they said ‘get out’! I wanted to calm them down, said that I wasn’t trying to destroy our relationship. I wanted us to work together for better education for deaf people. I know I’m from a different country, but I did feel really lost and wanted to move on but I experienced challenges. Really anyone like me, Black and deaf or just wanting to develop, we have to expect challenges. You can’t cover it up and pretend that everything in the UK is smooth and it’s all fine. I experienced a lot of threat. I worked hard to convince people who threatened me that I’m not a bad person, not a destroyer. It’s a really slow process to change people’s perceptions so that we can engage with each other.

Being an African migrant, he felt really lost and wanted to move on with his life but had to experience challenges along the way. He found some sense of community in a Christian church group which provided services with BSL access. Since the Black Lives Matter movement, more stories of racism within the British deaf community have emerged and expressed in the deaf media such as in talk shows. These are experiences that have rarely been documented in academic studies.

In additional, when Hawa and Samba emigrated from a country where the majority of people are black to the UK, they became ‘Black’ based on their skin colour being a minority in the country. While they experience intersectionality in ways that overlap with experiences of British-born black people, they had not only experienced racism, but also discrimination based on being a migrant.

Conclusion

Using intersectionality in context in mobility, Hawa and Samba’s narratives are exemplifying how their experience of audism interlocks with racism and gender-related and language-related oppression. These oppressions are explicitly linked to power structures in institutions (Home Office, education, work, church, and the family) which are important in the context of migration. An intersectional intercategorical lens can be ideal in making sense not only of one person’s experience, but also how power exists in institutions and renders marginalised and invisible people with less power and privilege.