By: Annelies Kusters and Jemina Napier, 14 September 2018

Annelies:

What do people think when they see a signing person on stage, and hear a simultaneous interpretation?

On Thursday 6 September, I gave a keynote presentation at BAAL titled “Sign multilingual and translingual practices and ideologies”. You can find the video here (click CC for subtitles): http://www.cvent.com/events/baal-2018-annual-meeting/custom-37-78e684777ce54042b0e7fd5e79f5dc7b.aspx

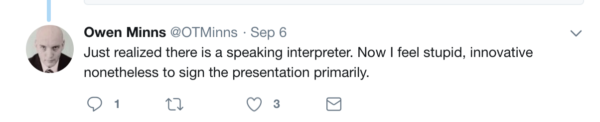

It was the first presentation of the conference and a number of people tweeted. One of the tweets read:

I wasn’t using a pre-recorded audio-file from which I was interpreting myself. I am a deaf scholar. I presented in British Sign Language and was interpreted into spoken English by Jemina Napier. This is the typical practice for deaf academics presenting at conferences. My deaf colleagues, the team of interpreters and I initially laughed at the misunderstanding, and the Tweeter also realised his mistake quickly, writing:

However, rather than just waving it away as the umpteenth ignorant comment about deaf people, another funny anecdote to share with my friends, this also made me think. I am in a pivotal moment in my academic career in that I’m becoming more visible. Did it even occur to the Tweeter that I was deaf, and that me signing my presentation in British Sign Language was not an attempt at being innovative but simply the best option at hand (sic) for me? In other words: why not assume immediately that this signing person on stage in a mainstream conference is most probably deaf? Do people not think that deaf people can be academics who can get invited as keynote presenters in this kind of conferences?

Example two. During one of the breaks at the same BAAL conference, another scholar from another British university approached me. He said he had seen me on the screen: the hall where the keynote happened was full and he was watching the livestream in another room. Apparently he initially thought I was speaking and signing at the same time, and was puzzled about my Australian accent. Only later, he realised that I was working with an interpreter (and if I would have an accent in English, a language I do write but not speak, it would certainly not sound Australian!).

Example three. After another applied linguistics conference where I gave a keynote earlier this year, the TLANG closing event, someone wrote about my keynote presentation “Her keynote was an especially engaging end to the day as it was impressively and seamlessly presented in both sign language and spoken English.“ At that conference, I was interpreted into English by Christopher Stone. A simultaneous interpretation is not a simultaneous presentation. (1)

Example four. I taught in a summer school in Denmark a few years ago. I was teaching in International Sign and two interpreters were interpreting into spokenEnglish. Several students thought that the interpreters were the teachers, and that I was the interpreter. And this was on (already) day three of the five day summer school. Go figure.

For the keynotes at BAAL and TLANG, I carefully selected the interpreters with whom I wanted to work. They have PhDs themselves and are scholars in the field of applied linguistics. I practiced my presentation several times in order to ensure it would be clear and smooth (which benefits the interpreting process). I went through the final powerpoint with the interpreters too. This is the background context to Jemina’s and Chris’ smooth interpretation at BAAL and TLANG. Maybe it sounded effortless. Like a pre-recorded audio file perhaps? This is in itself proof of how successful simultaneous interpretation can be when working with the right person, with the right background, with the right amount of preparation (2). I am extremely privileged to be able to work with them. I know too many deaf academics who aren’t so lucky to be able to work with expert interpreters who are also specialists in the deaf scholar’s academic field.

But what I’m trying to say is this: even though I was signing my keynote, my deafness might not be recognised. People might not realise that I’m being interpreted. And what does that mean for my identity as a deaf academic? Should I start presentations with a statement that I am deaf and working with an interpreter?

At mainstream conferences, presentations on signed languages are often only attended by other signed language researchers especially when they are grouped in one thread alongside multiple parallel presentations. Which means: we need to be in main panels. We need to be keynote presenters. We need to get out of that niche. Many keynotes on signed languages are delivered by hearing scholars who speak. We need visibility of signed languages. We need visibility of deaf scholars. I got out of this niche: I experienced very critical and proud moments in my academic career when I was asked as keynote presenter at mainstream language-related conferences. And still, I seem to have blended in to the absurd extent that some people don’t see who I am. Is this the opposite of tokenness? I am deaf. And I was signing my presentation.

Jemina:

I am the interpreter who interpreted Annelies’ signed keynote at BAAL. I have been practising as an interpreter since 1988, and have been an academic since I completed my PhD in 2002. I am now a Professor of Intercultural Communication at Heriot-Watt University, where I work alongside Annelies as one of my colleagues. Most of my interpreting work these days is in conference settings. I particularly enjoy the challenge of interpreting for deaf scholars giving presentations, as I want to ensure that I can represent them in spoken English: their personality, their ideas, their theories, their humour, etc.

I have only ever interpreted for Annelies once before, so I was honoured when she asked me to interpret her keynote. I had initially thought I might go to the BAAL conference as an attendee, but after Annelies asked me I agreed to go as an interpreter. This means when I am there I am in ‘interpreter mode’ – I don’t network with other academic colleagues, and I focus on doing the best job I can as an interpreter. Annelies and I know each other very well as we work together: I know her research and I understand her clearly, so I had no qualms about interpreting her presentation. But this didn’t mean we took anything for granted. We still spent a lot of time preparing – going through her powerpoint slides, where I queried her intentions, her use of terms, how she would sign things, and the ultimate goal of her presentation. These are typical preparation strategies that any good interpreter would use.

So when I interpreted for her presentation at BAAL, I was confident I could represent her well. And it did go well. I gave a smooth delivery, and with the support of my co-interpreter Christopher Stone, no stone was left unturned in her presentation. Interestingly, when it was finished, several of the other working BSL interpreters, and an interpreter who was an audience member, all commented on what a good job I had done. Another non-signing member of the audience approached me during the break to ask if I was the interpreter who had interpreted Annelies’ speech and told me how much she enjoyed listening to me. My response to all of them was that it was good, because Annelies gave an excellent presentation, and I did a good job because Annelies and I prepared together. Although it is nice to receive compliments on your work I still felt uncomfortable because it should be Annelies receiving the praise not me. I was only there because she was the keynote. They weren’t my words – they were hers – presented through signs. I was her ‘voice’. But she was the ‘performer’.

In conversations with Annelies and other colleagues afterwards it made me reflect on why people wanted to congratulate me on my interpretation. Is it because they rarely hear such a smooth interpretation of a deaf presenter? Is it because deaf keynotes are still so rare? (3) Did it occur to them how much time and effort Annelies and I put in to make sure that it would be an effective presentation and interpretation? Why is it that interpreters seem to get more attention than the presenters themselves?

Ironically, I am involved in a research project with Professor Alys Young and Rosemary Oram from the University of Manchester, where we have coined the term ‘the Translated Deaf Self’, which explores these exact issues – how deaf people feel about being ‘known’ through translation, and also how interpreters feel about having the responsibility to represent deaf people through translation. Our project, funded through an Arts & Humanities Research Council Translating Cultures Theme Research Innovation Grant and Follow-on Funding for an art exhibition to ‘translate’ the results into artworks (see https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/artviatds/about/map/), sought to explore how translation might actually be constitutive of deaf cultural identity through the shared experience of being translated, and also the potential impact of experiencing existence to others as a translated self or selves.

In the BAAL example, I was not just translating Annelies’ deaf self, I was translating her academic self – she wasn’t performing as a deaf person, she was performing as an academic – but the fact that she was signing brings focus to the fact that she is deaf. Or does it? Given the tweet and comments from hearing, non-signing audience members, it seems that some people might have assumed that she was a hearing person being innovative by signing. I have been one of those people: I have signed when presenting at a mainstream translating and interpreting conference – where there were some deaf members of the audience – to make a point that people often don’t consider sign language when they discuss translation and interpreting generally. It got a very positive response. But it made me uncomfortable, as I discussed in a blogpost shortly afterwards (see http://lifeinlincs.org/?p=2215in English and International Sign), as although my choice to sign highlights the validity and vitality of signed languages, I was regarded with esteem as a hearing person presenting in sign language. Would I have received such a positive response if I hadn’t signed? But ultimately I had a choice. Annelies didn’t have a choice. She is a deaf person, and she signs. But she deserves esteem as an academic, and the fact that she was invited as the keynote seems to have been overlooked, or overclouded by the sign language aspect. She was being translated, but at the end of the day should it matter? What she has to say as an invited speaker is surely more important. The results of our Translated Deaf Self project due reveal, however, that it is not as simple as that. And we have seen the evidence of that in practice.

Footnotes

(1) That would be a situation where two presenters stand next to each other: one signing in one language, and the other either speaking or signing in another language – and some colleagues have experimented with this model.

(2) There have been some interesting research studies about that eg a forthcoming article by De Meulder, Napier, Stone; Napier, Carmichael & Wiltshire discussed a case study of a deaf presenter and interpreters working together.

(3) We could only think of one other keynote given by a deaf academic at a mainstream conference – Robert Adam at the International Conference on Minority Languages in 2017.