Text: Erin Moriarty Harrelson

Videos: Amandine le Maire

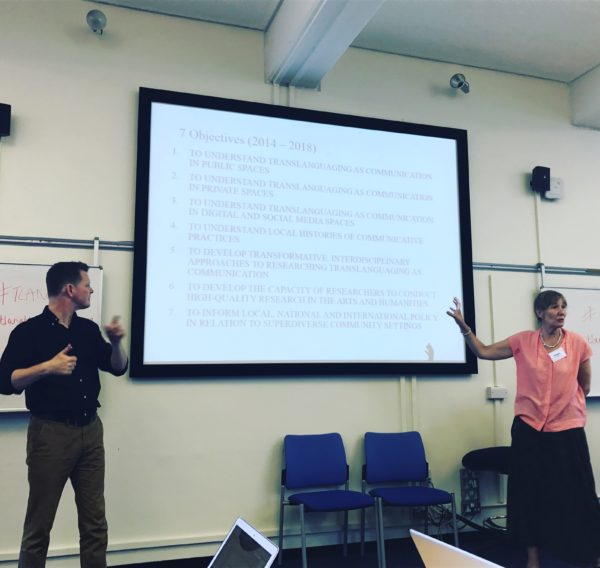

Last week, we (Amandine le Maire and Erin Moriarty Harrelson: two of the four MobileDeaf project researchers), traveled to Birmingham for a 5-day residential course at the University of Birmingham organized by TLANG, Translation and Translanguaging: Investigating Linguistic and Cultural Transformations in Superdiverse wards in Four UK Cities. TLANG is a collaboration of seven universities and seven national non-university partners that aims to investigate how people communicate in increasingly diverse city settings and its implications for policy and practice. This course was designed for researchers who are engaged in communication in multilingual contexts, a perfect fit for the MobileDeaf project researchers.

Translanguaging theory offers different understandings of how people communicate with other people, especially without a shared language. Language is not a bounded entity, nor is it limited to spoken words or signs. Communication includes things that are not always considered part of a “language,” such as gestures, pointing, the use of space and objects, drawing, etc. Translanguaging theorizes the various elements involved in everyday communicative practices as part of an individual’s repertoire and examines the semiotic resources available to people and how they are used in specific spaces. Thinking of communicative practices and the different ways people co-construct understanding as “languaging” allows for flexibility, especially for people who are members of a marginalized language group.

Over the course of the week, we worked with a diverse group of approximately 44 researchers from 22 countries, including a large delegation from South Africa. Translanguaging theory came alive throughout the week as we worked on projects with colleagues from South Africa, Sweden, Brazil, and the United States.

Translanguaging in Practice

On the third day, we were asked to give an impromptu presentation about our languaging practices throughout the course. Many of the delegates had questions about the interpretation process and the role of the British Sign Language/International Sign-English interpreters so Professor Angela Creese asked us to briefly describe our experience with translanguaging. We explained that we were both new BSL learners, fluent in different written languages (French and English), as well as other signed languages such as American Sign Language, Cambodian Sign Language, Belgian-French Sign Language and International Sign. One of the interpreters, Andrew Carmichael, is a certified International Sign interpreter, a fluent BSL signer, and knows some ASL; the other interpreter, Emma Dunleavy-Dale is fluent in BSL but not International Sign or ASL. This presented an interesting situation where everyone involved worked together on co-creating meaning/understanding through fingerspelling in ASL, which is very different from the two-handed BSL fingerspelling, pointing to the PPT, and a mixture of ASL, BSL and IS. For example, Erin relied more on the PPTs in English to follow the lectures, whereas Amandine relied more on the interpreters. The other delegates were fascinated by this process and the use of multimodal visuality in our languaging practices.

An especially interesting interaction happened during lunch on the second day. We decided to have lunch outside underneath the shade of a large tree. As we chatted in ASL and BSL, a member of the Brazilian delegation came over and asked if he could join us. This turned into a fascinating example—one of many that popped up throughout the week—of translanguaging in action. Erin can read lips in English so she carried on a conversation with Rafael, interpreting from Rafael’s spoken English into ASL for Amandine, who is fluent in French but had not gotten used to lip-reading in English yet. Rafael used gestures and spoke in English, Erin translated into ASL/BSL for Amandine, using a combination of the two languages because both know ASL and are in the process of learning BSL. Erin then responded to Rafael in written English on her iPhone. If Erin missed a word on Rafael’s lips, he used his own iPhone to type out the word in English. As the conversation progressed, we found out that Rafael also spoke French, so he started speaking French so Amandine could lip read him but it was challenging for her because she was used to how French is spoken in Belgium, which has very different lip movements. It was a robust conversation, thanks to multimodal translanguaging, that reflected what we had been discussing during the workshops. We were able to talk about our backgrounds, the languages we used, and our academic interests.

Methodologies: A deaf lens

During a workshop led by Professor Adrian Blackledge, Translanguaging and the Body, it was clear that we were able to easily recognize and analyze various data sets because of our lived experience of visuality and multimodal languaging. Adrian showed a short film clip of a brief interaction that included a communication “break-down” between two participants at a service counter in a public library. Amandine recognized the meaning of one of the participants’ gestures, contributing to new insight for the group. As deaf researchers, our experience with visual communication modalities allowed for new insights into data analysis.

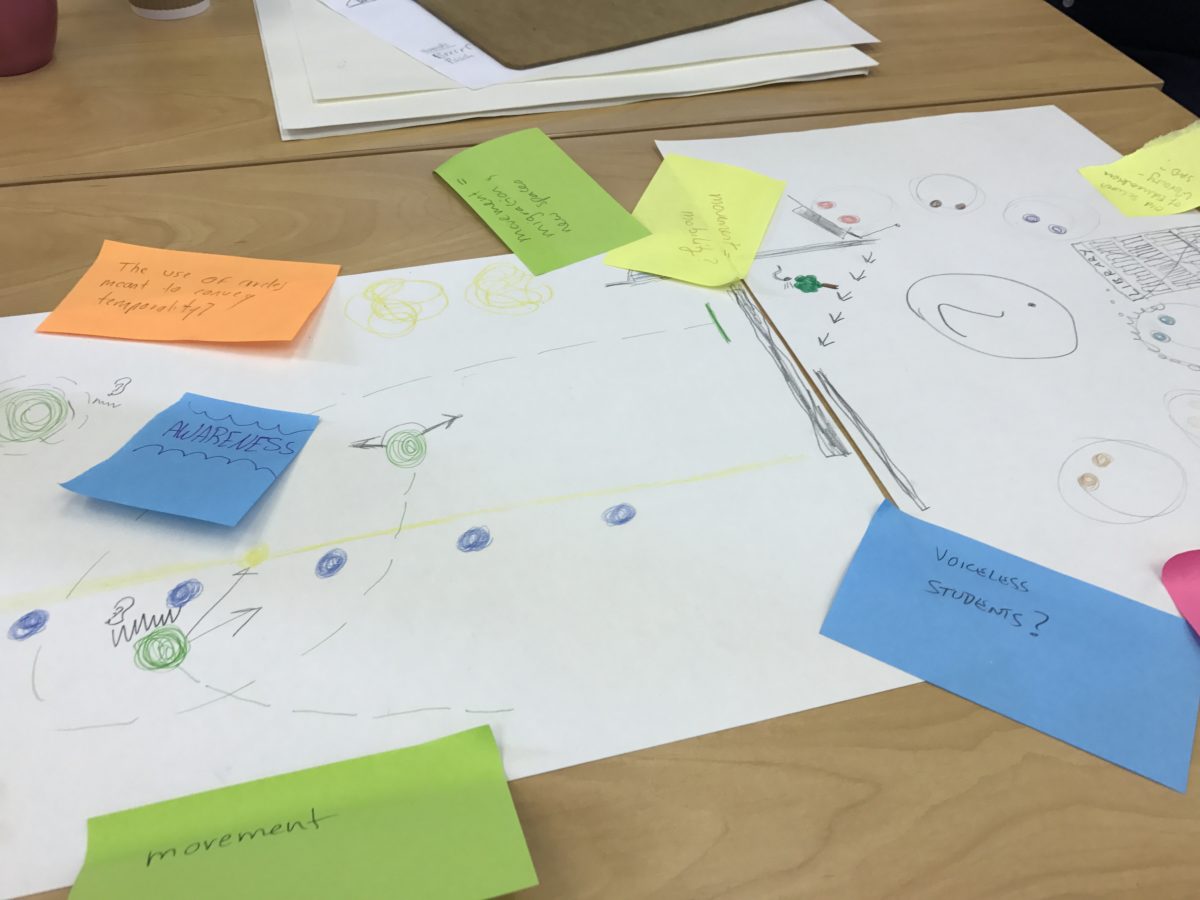

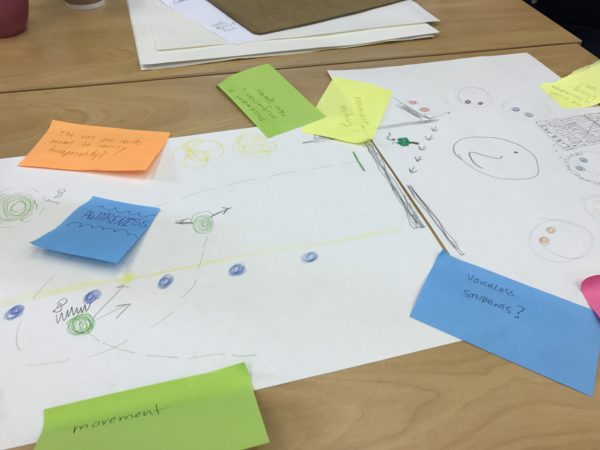

We found the workshop on visual methodologies especially thought-provoking. We had already used some of the approaches to data collection, e.g. collecting drawings from deaf people, but this workshop pulled all of the threads together. One of the things we found most interesting was the use of drawings to map the movement of people in a given space, such as the preference for a certain door over others, and drawing/mapping as a way of eliciting data, such as asking people to draw a map of a space that’s important for them, to get insight in how people perceive and experience these spaces. These methodologies are especially useful for MobileDeaf as we study mobility and how deaf people move through spaces, as well as use spaces and the things available in those spaces as a part of their communicative repertoire.

We were inspired by this summer school and returned to Edinburgh with new ideas for our individual projects. The knowledge we gained from this course and the interactions with our colleagues gave us resources we will use as a team as we move forward with our research.

We were inspired by this summer school and returned to Edinburgh with new ideas for our individual projects. The knowledge we gained from this course and the interactions with our colleagues gave us resources we will use as a team as we move forward with our research.